What science says about animal agriculture and climate change

As we try to tackle the climate crisis, animal agriculture is the elephant in the room. Scientists have proven that raising livestock is one of the largest causes of greenhouse gas emissions.

But why? How? And how much? If we as a species are to survive, it is now critically important that everyone – from ordinary people to government officials – asks these questions and understands the answers.

The debate has barely entered mass consciousness, but it is already highly polarised and politicised. On one hand, animal rights zealots and radical conservationists shriek that it’s a moral issue. On the other, the multi-billion-dollar animal agriculture industry uses its army of paid lobbyists and public relations staff to obtain huge subsidies, sway government policy, suppress public awareness and promote disinformation about so-called “sustainable” practices that serve only to greenwash the destruction.

This website does not discuss the connection between meat and public health, pandemics, biodiversity, pollution, hunger and animal welfare. It’s not an attempt to turn you into a militant vegan. It seeks simply to present a sober, evidence-based explanation of how animal agriculture affects climate change.

It is the burning issue of our time.

From rainforest to Big Mac: following the emissions trail

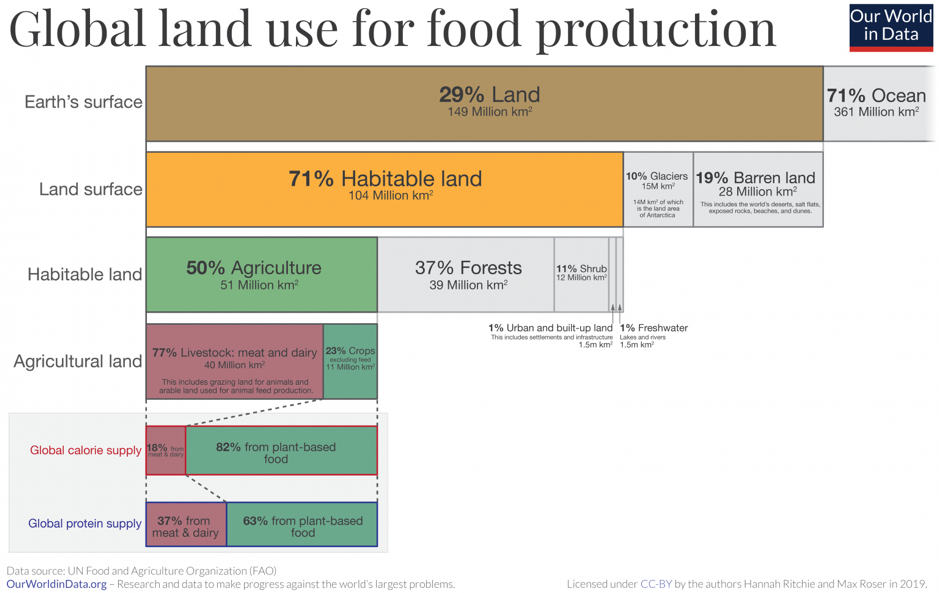

As the world population grows and incomes in developing countries rise, the demand for meat is soaring. But feeding crops to animals that we slaughter later, rather than just eating the plants ourselves, is a very inefficient way for humans to get nutrition. The 77% of agricultural land used to feed and graze livestock produces only 18% of global calories and 37% of protein. To get protein from meat rather than soybeans takes between six and 17 times the land, between 4.4 and 26 times the water, and from six to 20 times the amount of fossil fuels.1

According to the UN, livestock production – growing feed crops and grazing – now occupies 30% of the entire land surface of the planet, and accounts for 77% of agricultural land.

The land now used for animal agriculture was mostly forest and savannah that provided a natural carbon sink. That land has now become a carbon spigot. Fossil fuels are used throughout the supply chain – clearing land, planting, harvesting and transporting feed crops, making and applying fertilisers and pesticides, heating and cooling buildings, processing and refrigerating animal products, and transporting them to the consumer.

Huge amounts of greenhouse gases – particularly methane and nitrous oxide, which are exponentially more harmful than carbon dioxide2 – are emitted by enteric fermentation (livestock burps and farts) and decomposing manure.

Vast quantities of feed are required for livestock, and in many parts of the world, the waste from feed crops is eliminated by fire, emitting more greenhouse gases. Massive amounts of fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides are used to grow the feed; the run-off poisons waterways and oceans. (Dybas, 2005); in particular, the nitrogen in fertiliser is primarily responsible for ocean dead zones. This pollution turns seawater turns more acidic, reducing the amount of carbon it can absorb from the atmosphere. The vicious cycle is reinforced on land, too, as agriculture degrades the land, causing soil erosion and desertification3, destroying the carbon sink still further.

In the following sections, we will look at each of these processes more closely.

Or jump to:

- From carbon sink to carbon spigot

- Ruminating on methane

- Feeding the beast

- Hogging the water

- Mountains of manure

- Fertiliser and pesticide

- Processing and transportation

- Land degradation

- Gross inefficiency

REFERENCES

-

1.Reijnders S. Quantification of the environmental impact of different dietary protein choices. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 78, Issue 3, pp. 664S–668S. Published 2003. Accessed 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/78.3.664S

-

2.Shindell DT, Faluvegi G, Koch DM, Schmidt GA, Unger N, Bauer SE. Improved Attribution of Climate Forcing to Emissions. Science. Published online October 29, 2009:716-718. doi:10.1126/science.1174760

-

3.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change . Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. In press; 2019:12.